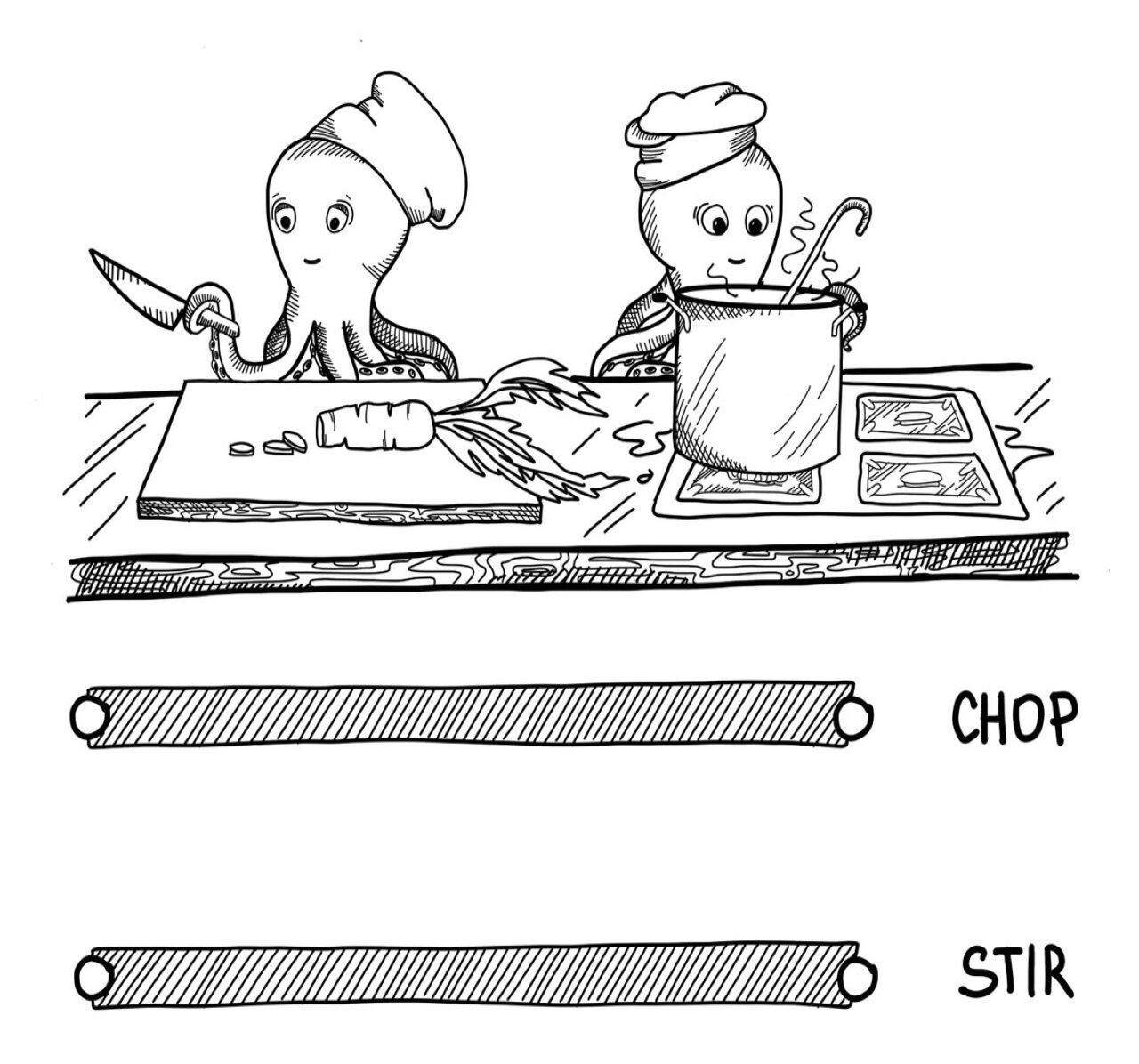

Introducing Concurency

In computing, concurrency is the ability to handle multiple tasks at once. Concurrency, simply put, is about tasks that start, run and complete in overlapping time periods, in no specific order.

Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world. - Nelson Mandela -

Concurrency Vs Parallelism

Parallel computing or parallelism, often confused with concurrency, is the simultaneous execution of tasks at runtime and it requires hardware with multiple computing resources.

Concurrency is about dealing with lots of things at once. Parallelism is about doing lots of things at once. - Rob Pike -

Goroutines

Goroutines, are the functions that can run concurrently with the rest of the code. Goroutines are dissimilar to threads in the fact that goroutines are less expensive to create, can communicate with each other using channels and they can run on a single OS thread.

To create a goroutine, create a normal function and add the go keyword when calling it.

func nowthatshot() {

fmt.Println("maybe slow")

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

fmt.Println("fine im done")

}

func main() {

fmt.Println("start")

// Create a goroutine to do something slow

go nowthatshot()

fmt.Println("waiting for the slow func")

time.Sleep(500 * time.Millisecond)

fmt.Println("Finished the main task!")

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

}Result

start

waiting for the slow func

maybe slow

Finished the main task!

fine im doneChannels

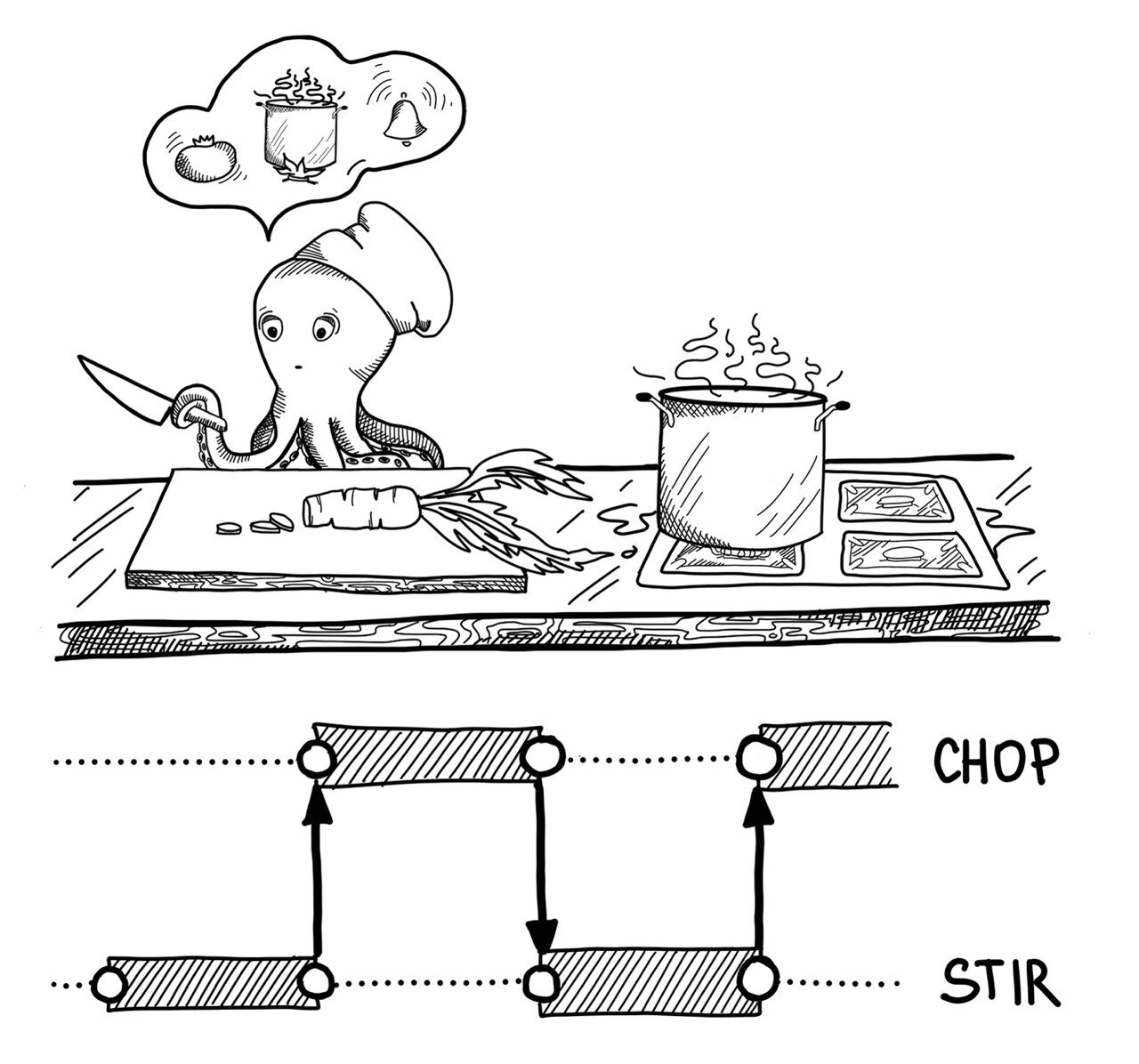

If we talk about concurrency in Golang, Golang provides us with a type of concurrency called Channel. Simply put channels help communicate between Goroutines. We can send and receive information from one Goroutine to the other.

Go has two types of channels:

By default channels are unbuffered, meaning that they will only accept sends (chan <-) if there is a corresponding receive (<- chan) ready to receive the sent value. Buffered channels accept a limited number of values without a corresponding receiver for those values.

Unbuffered Channels

A channel is a communication vessel used by goroutines to interact with one another. As stated before by default Channels are unbuffered, meaning they cannot hold information. Consequently, if an unbuffered channel receives some data it has to immediately send it somewhere.

Let’s look at this example

import "fmt"

func main(){

ch := make(chan int) // Making a channel that takes in integers

ch <- 10 // the value 10 is sent to the channel, this the channel's sender

v := <- ch // the variable v receives the channel's value, this is the receiver

fmt.Println("Received", v)

}The program will get stuck on the channel send operation waiting forever for a goroutine to access it.

This is called a deadlock, a deadlock happens when a group of goroutines are waiting for each other and none of them is able to proceed.

It’s like playing hot potato but you’re the only person playing with no one to hand the potato to, you would lose immediately.

A workaround deadlock is to add a goroutine

import "fmt"

func main(){

ch := make(chan int) // Making a channel that takes in integers

// Created a goroutine that contains the sender

go func(){

ch <- 10

}()

v := <- ch // the variable v receives the channel's value, this is the receiver

fmt.Println("Received", v)

}In the above code snippet, we only have 1 goroutine and channels require 2 goroutines to operate. Well, the code does actually contain 2 goroutines. The first is the go func and the second is the generated goroutine.

Buffered Channels

Unlike unbuffered channels, buffered channels have a capacity attribute, meaning they can hold an n number of values.

import "fmt"

func main(){

ch := make(chan int, 1) // Created a buffered int channel that can hold one value

fmt.Println("Sender")

ch <- 10 //Creating a sender

v := <- ch //Creating a receiver

fmt.Println("Received", v)

}Contrary to unbuffered channels, the code snippet won’t result in a deadlock. This is because the sender of a buffered channel only blocks when the channel is full - while the receiver only blocks when the channel is empty.

The added attribute of buffered channels creates a new problem, let’s look at it with this simple example.

import "fmt"

func main(){

ch := make(chan int, 1)// Creating a buffered int channel capable of holding one value

fmt.Println("First Sender")

ch <- 10

fmt.Println("Second Sender")

ch <- 11

fmt.Println("First Receiver: ", <- ch)

fmt.Println("Second Receiver: ", <- ch)

}Running the code will result in a deadlock, the sender is infinitely blocked. This is because the channel is full and got sent another value before the channel is freed up.

This problem can be solved by either increasing the capacity of the channel

package main

import "fmt"

func main(){

ch := make(chan int, 2)// Creating a buffered int channel this time capable of holding two values

fmt.Println("First Sender")

ch <- 10

fmt.Println("Second Sender")

ch <- 11

fmt.Println("First Receiver: ", <- ch)

fmt.Println("Second Receiver: ", <- ch)

}How it handles multiple data The buffered channel data is stored in a FIFO queue meaning the first value sent to the channel is the first one to leave the channel.

The problem could also be solved by adding a Goroutine

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

ch := make(chan int, 1) // Making a channel that takes in integers

// Created a goroutine that contains the sender

go func() {

fmt.Println("Sent: 10")

ch <- 10

fmt.Println("Sent: 11")

ch <- 11

}()

v := <-ch

fmt.Println("Received", v)

v = <-ch

fmt.Println("Recived", v)

}Got It

Concurrency is one of the strengths that make Go so powerful and popular. Goroutines are the power of concurrency in go, they are functions that can run concurrently. Channels are how these goroutines can send and receive data between each other.